Children worldwide are substantially heavier than in previous generations, and childhood obesity is a major global public health concern. The frequency of obesity among children and adolescents has increased by 47% during the previous three decades [1]. According to recent prevalence estimates of 23% and 13%, respectively, there have been increases in industrialized and developing nations [1]. Obesity rates may have plateaued among young children in wealthy nations. Still, they remain excessively high, having negative short- and long-term effects on children’s physical, psychological, social, and economic well-being [2][3][4].

It is estimated that 38.2 million children under five were reportedly overweight or obese in 2019. Overweight and obesity, formerly considered an issue only in high-income nations, are increasingly becoming more prevalent in low- and middle-income nations, especially in metropolitan areas. Since 2000, there has been a nearly 24% increase in the proportion of under-5-year-old overweight children in Africa. In 2019, Asia was home to over half of the world’s young, overweight, or obese children [5].

Is Obesity Really a Problem?

Children and adolescents affected by the significant medical disease known as childhood obesity are especially concerning because childhood obesity frequently sets kids up for health issues like diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol, formerly thought to be the domain of adults. Additionally, sadness and low self-esteem in children can result from obesity.

Furthermore, weight bias, the stigma associated with people considered obese, is a very serious issue in adolescents as it sets them up for bullying. Despite research pointing to the importance of hereditary factors, health, and social contexts, people frequently blame these people for their weight status. Consequently, those who are obese, according to medical standards, are frequently characterized as unmotivated, uneducated, and lazy.

Being treated unfairly because of your weight increases the risk of developing eating disorders, depression, and inactive lifestyle habits [6].

Body Mass Index (BMI)

The body mass index (BMI) is the most often used parameter to compare weight and height. It tries to assess body fat using height and weight. People are then classified as underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese, or severely obese based on the resultant number. However, BMI is imperfect since it does not consider other elements that affect body composition, such as age, muscle mass, or sex. For instance, BMI estimations may overstate body fat in elderly individuals or athletes [7].

BMI categories for adults

- Underweight is a BMI of less than 18.5

- Healthy weight is a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9

- Overweight is a BMI of 25 to 29.9

- Obesity is defined as a BMI of 30 or above.

BMI categories for children

Height and weight for children are displayed in percentiles. By comparing a kid’s BMI to growth charts for children of the same age and sex, the BMI percentile for that child is determined.

Use the BMI percentile calculator from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for Kids and Teenagers to determine your child’s percentile.

Causes of Obesity in Children

Image source: fitnessforhealth

Several factors that typically work in concert affect your child’s likelihood of being overweight:

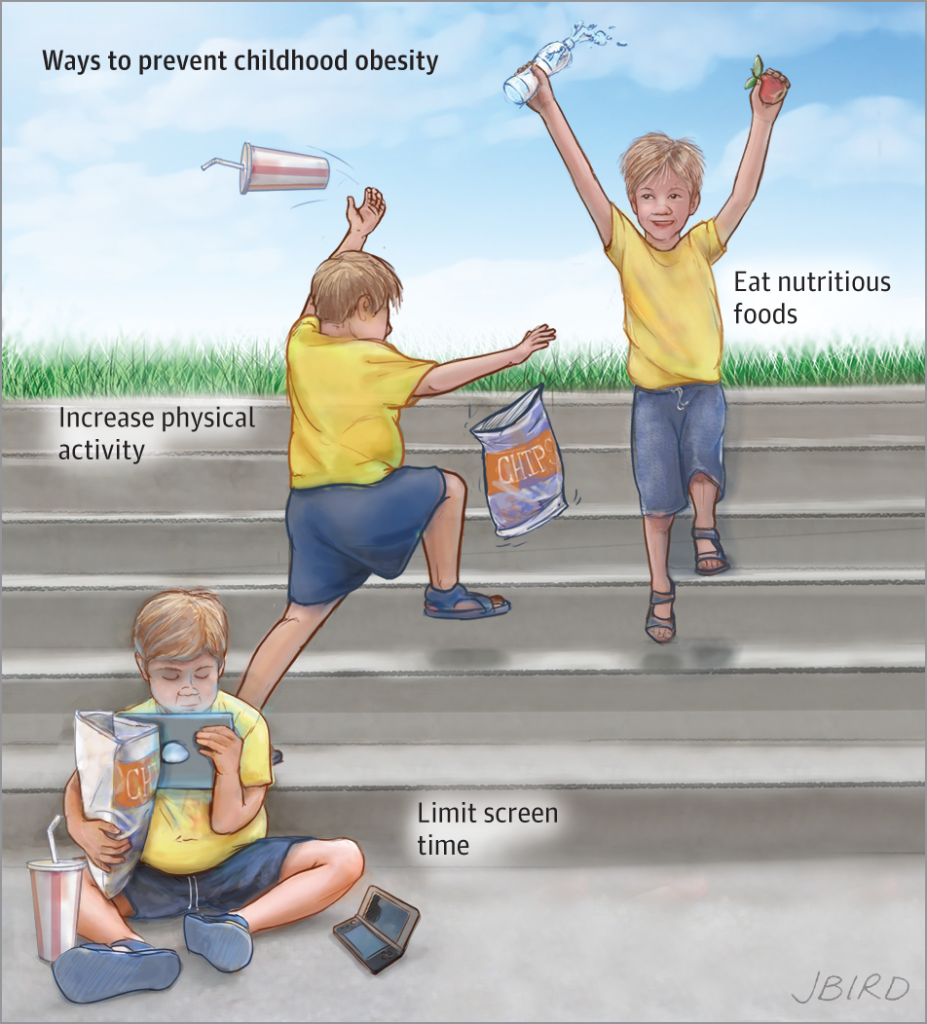

- Diet: Your child may put on weight if they consume high-calorie items on a regular basis, such as fast food, baked goods, and vending machine snacks. In addition to candy and pastries, there is growing evidence that sugary beverages, such as fruit juices and sports drinks, are to blame for some people’s obesity.

- Lack of Exercise: Because they don’t burn as many calories, kids who don’t exercise a lot are more likely to acquire weight. The issue is further exacerbated by spending too much time doing sedentary activities like watching television or playing video games. TV programs frequently include commercials for harmful meals.

- Family history: Your child may be more prone to gain weight if they come from an overweight family. This is particularly true in settings where calorie-dense meals are constantly available and physical activity is discouraged.

- Psychological factors: Personal, parental, and family stress may increase an obese child’s risk. Some kids binge eat to get through difficulties, manage emotions like stress, or get rid of boredom. Perhaps their parents exhibit similar inclinations.

- Socioeconomic factors: People in certain places have little access to stores and little money. As a result, individuals could purchase shelf-stable convenience items like frozen dinners, crackers, and cookies. Additionally, residents of low-income areas might not have access to a secure gym.

- Certain Medicines: The risk of becoming obese can be raised by several prescription medications. They consist of propranolol, lithium, amitriptyline, paroxetine (Paxil), gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise), and prednisone (Inderal, Hemangeol).

Symptoms

Not all overweight children have excess weight. Some kids have bigger-than-average frame sizes. Additionally, children often have varying levels of body fat depending on their developmental stage. Therefore, it’s possible that you can’t tell if your child’s weight is a health risk from the way they appear [8].

The established indicator of overweight and obesity is the body mass index (BMI), which offers a weight-to-height ratio. Your child’s doctor can help you determine if your child’s weight might cause health issues by using growth charts, the BMI, and, if required, additional testing.

When to See a Doctor

Speak with your child’s doctor if you are concerned that they are gaining too much weight. The doctor will take into account your child’s growth and development history, your family’s history of weight-for-height, and where your child stands on the growth charts. This might aid in figuring out whether your child’s weight is within harmful bounds.

Diagnosis & Treatment

The doctor assesses your kid’s BMI as part of routine well-child care and determines where your child stands on the BMI-for-age growth chart. Treatment Includes;

- Healthy Eating Habits

- Physical Activity

- Medications

- Weight Loss Surgery [8]

How Much Physical Activity Do Children Need?

Image source: Pinterest

The amount of physical activity required for optimum health is detailed in the WHO guidelines and recommendations for various age groups and particular demographic groups. According to the WHO, physical activity is any skeletal muscle-driven movement involving energy use. All movement, whether done for recreation, transportation to and from locations, or as part of a person’s job, is considered physical exercise. Both intense and moderate physical activity is beneficial to health.

Walking, cycling, wheeling, sports, active recreation, and play are all common ways to be active that anybody may do for fun and at any ability level.

For kids under the age of five

Infants (less than one year) should:

- Exercise often throughout the day, preferably via participatory floor-based play; the more, the better. This involves at least 30 minutes of prone time (tummy time), dispersed throughout the day for infants who are not yet mobile, not being strapped to a caregiver’s back, placed in a high chair, or other forms of restraint for more than one hour at a time. Screen time should be limited.

- When inactive, reading and storytelling aloud to a caregiver are encouraged, and babies should get 14–17 hours of excellent sleep (0–3 months) or 12–16 hours (4–11 months), including naps.

On a 24-hour day, children between the ages of 1-2 should:

- Distributed throughout the day, engage in a range of physical activities for at least 180 minutes at any intensity, including moderate- to vigorous-intensity bodily exercise.

- Not sit for prolonged amounts of time or be confined for longer than an hour at a time (e.g., in high chairs, strapped to a caregiver’s back, or in strollers).

- Sedentary screen time, such as watching TV or movies or playing video games, is not advised for children under one.

- Less is preferable for sedentary screen time for children under two—no more than one hour.

- Enjoy 11–14 hours of restful sleep, including naps, at regular periods.

On a 24-hour day, children between the ages of 3 and 4 should:

- Distributed throughout the day, engage in at least 180 minutes of physical activity of all kinds, at any intensity, with at least 60 minutes being moderate- to vigorous-level physical activity; more is preferable.

- Not sit for prolonged periods or be constrained for longer than one hour at a time, such as in strollers or pushchairs.

- Less is preferable regarding the recommended hour of sedentary screen usage.

- Encourage reading and sharing stories with a caregiver when sitting and

- Get 10–13 hours of high-quality sleep with regular sleep and wake-up times—possibly including a siesta.

Children and teenagers between the ages of 5 and 17

- Exercise for at least 60 minutes daily, five days a week, of moderate-to-vigorous intensity, primarily aerobic activity.

- It should include at least three days per week of high-intensity aerobic exercise and exercises that build bone and muscle.

- They should reduce their inactive time, especially spent on screens for fun [9].

Community-based interventions to promote physical activity

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health have concluded that community-based strategies are crucial for combating childhood obesity. Children are more likely to be prevented from becoming obese by community-based intervention programs that include schools and concentrate on both nutrition and physical activity, according to a comprehensive evaluation of childhood obesity prevention programs. Communities can facilitate people’s participation in physical activity [10].

More comprehensive treatments are undoubtedly preferable for gauging the effects of community-based initiatives on childhood obesity, according to Sara Bleich, Ph.D., associate professor of health policy and management. “The research demonstrates that since the environment is a significant factor in obesity risk, we must concentrate on both nutrition and activity in the areas where children live and attend school to help prevent obesity among youngsters. Children should pay extra attention to their neighborhood since they often have little or no control over it [10].

The following are some methods by which communities may encourage adolescents and their families to be physically active:

- Conduct Community-Wide Campaigns

Spread the word about physical exercise to children and families via radio, newspapers, billboards, television, and radio [11].

- Make Changes That Make It Easier to be Physically Active

- Allocate money to construct and connect bicycle lanes, crosswalks, and sidewalks.

- Create curb cuts so that wheelchairs, strollers, and cyclists may easily navigate roadways.

- Install traffic signals to slow cars down and improve safety.

- Finance and encourage walking routes or trails in the neighborhood’s local green spaces.

- Find and encourage safe methods to ride and walk to school. Assist people in finding places where they can engage in physical activity.

- Let community members and organizations use school gymnasiums, playing fields, and playgrounds outside of school hours.

- Promote the provision of youth physical activity programs through neighborhood groups. Community organizations can collaborate with schools to provide physical education after school events and programs.

- Work with Schools to Increase Youth Physical Activity

- To encourage physical activity programs in schools, colleges, universities, hospitals, health departments, companies, and community organizations may collaborate. A staff member may be encouraged to contribute their time to running physical exercise programs or events and provide funds or equipment.

- Community-based groups may provide transportation to off-site activities or after-school physical exercise programs at local schools.

- Community groups may support Safe Routes to School initiatives and take part in them, which aim to increase the number of kids who ride their bikes and walk to school.

- Partner with Other Community Groups

- Promote tales about physical exercise in your community’s media.

- Hold a bike rodeo to encourage safe cycling habits.

- Turn a local field or vacant lot into a park, ball court, or playground area.

- Collaborate with neighborhood groups to organize unique physical activity occasions like field days or fun races [11].

Post Disclaimer

The information contained in this post is for general knowledge purposes, composed of personal experiences and theoretical research. It should, in no way, be construed as professional medical advice. Kindly contact a trained and licensed practitioner if you need personal and professional counsel.